«Embroi(die)ry»

Exhibition

“After Love,” Golosova, 20, Tolyatti

“I ask my mother: how was love expressed in our family? How did the older women show it? My grandmother? My great-grandmother?”

“It wasn’t expressed at all,” my mother replies. “It didn’t manifest as love, but rather as survival. The meaning of love was—to survive.”

I embroider this phrase on a tablecloth that my great-grandmother hand-sewed and embroidered, which was used by three generations of my family.

The collages “Grew as Best I Could” are glued and embroidered onto the fabric of a household T-shirt. They are a reflection on childhood and adolescence.

On the left: Major Tom

On the right, top: Happy Childhood

Bottom: Adolescent

in collaboration with Gala Izmailova

Exhibition

“Where No One Dreams: from Sacred Geography to Non-Place,” MMOMA, Moscow, 2017

Alyona: For me, the most important thing when moving to another city turned out to be my old film camera, a gift from my father. To be honest, I hardly use it, but I took pictures with it the last time my father and I went hiking, and it was important for me to have it with me. During the move I wrapped it in everything I could, to keep it safe. And although it already has its own hard case, my anxiety was stronger than my trust in Soviet manufacturers.

Gala: When I moved to Moscow, I didn’t yet know that I would go through four relocations in three months. There were a few more things each time, and I was very anxious. Again and again I had to pack and unpack my belongings, sometimes without even having had the chance to use them. Perhaps only the monotonous process of wrapping one thing after another helped me to find balance.

Exhibition

Youth. Color, Department of Contemporary Art, Tolyatti Art Museum

Chosen by mutual agreement, a safe word creates a sense of trust and security, the possibility of ending any exchange at any moment.

Today, however, words meant to serve this protective function have lost their strength. Outside of clear agreements, it is difficult to feel fully safe. Too often, people ignore words like “no” or “stop,” crossing into another’s space, imposing their opinions, speaking without care for the possibility of causing hurt.

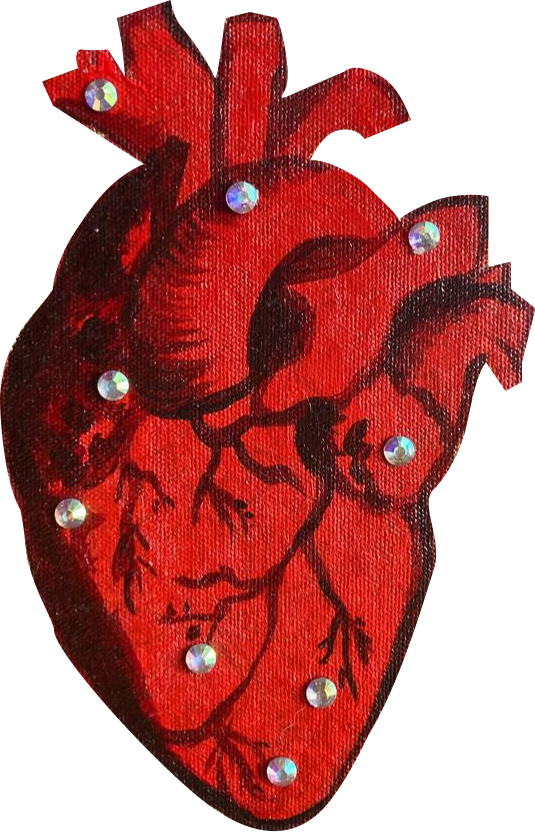

The artist invites us to take a sign for ourselves—as a reminder to be mindful of our words; to give one to a partner, friend, or even a parent who oversteps boundaries; to carry it as a reminder that not everything must be endured, heard, or felt. There is always a safe word. And if no other word works, let it be red.